Linear Regression - Analytical Solution and Simplified Example

- 5 minutes read - 883 wordsIntroduction

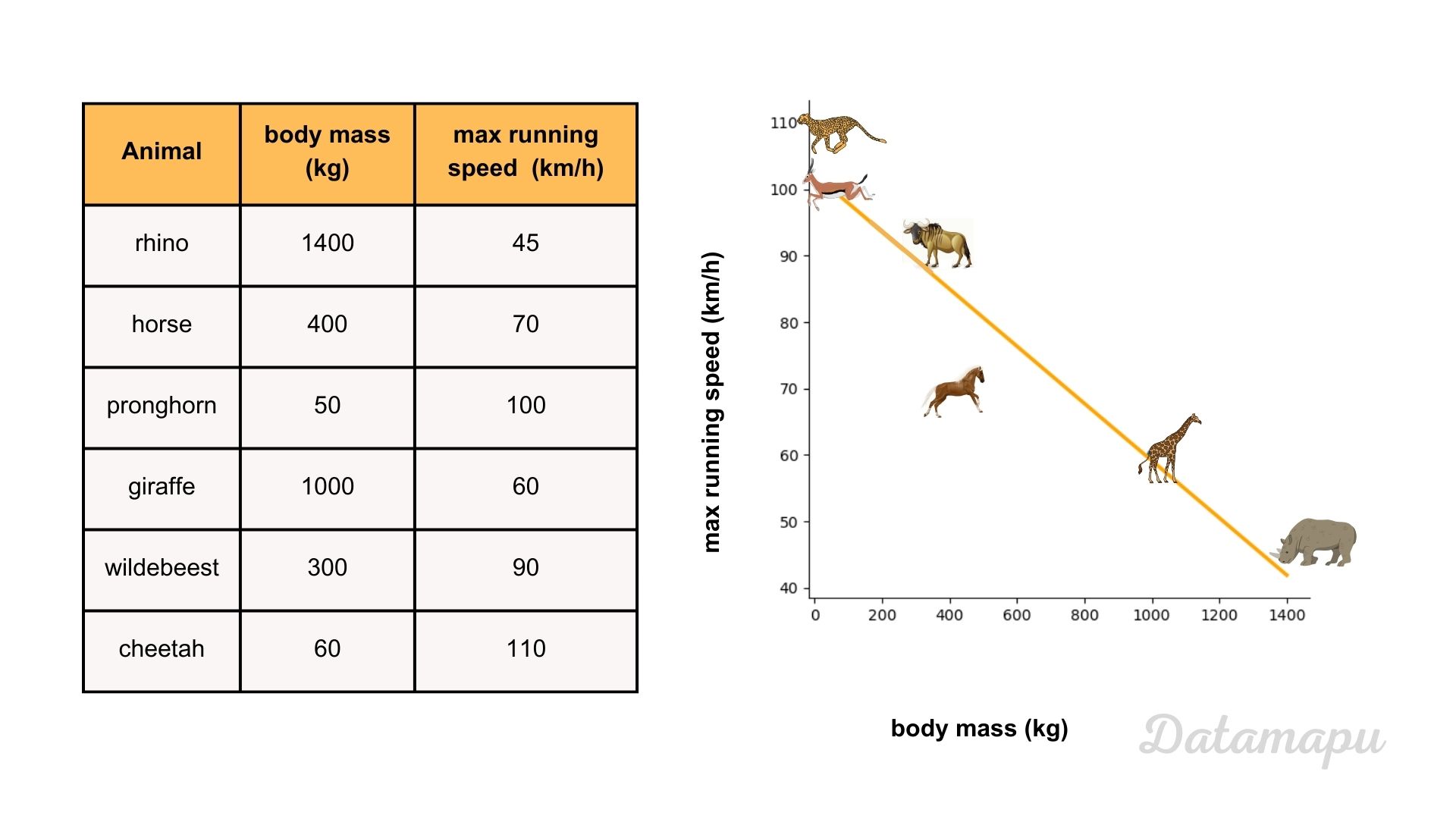

In a previous article, we introduced Linear Regression in detail and more generally, showed how to find the best model and discussed its chances and limitations. In this post, we are looking at a concrete example. We are going to calculate the slope and the intercept from a Simple Linear Regression analytically, looking at the example data provided in the next plot.

Illustration of a simple linear regression between the body mass and the maximal running speed of an animal.

Illustration of a simple linear regression between the body mass and the maximal running speed of an animal.

Fit the Model

We aim to fit a model that describes the relationship between the body mass (independent variable / input feature

with

Minimize the Loss

In real applications optimization techniques, such as Gradient Descent are used to estimate the minimum of the Loss Function. In this article, we will calculate the coefficients

Setting these equations to zero and multiplying both sides with

We will start with the second equation and resolve it for

with

Now, we continue with the first equation and resolve it for

We use the equation we resolved for

With that, we can calculate the coefficients

Note, as we know from calculus setting the first derivative, i.e. the gradient to zero is not a sufficient condition for a minimum. For this example, we assume that the only location with zero gradient is a minimum. To be sure that this is really a minimum we would need to check all second derivatives. At this point, it could also be a maximum or a saddle point. This is however not the scope of this article.

Example

We now use the data presented above to determine the linear relationship between the size and the speed of an animal, represented by

with

This results in

With that we can calculate

which gives

rounded up to 3 digits. With this we can calculate

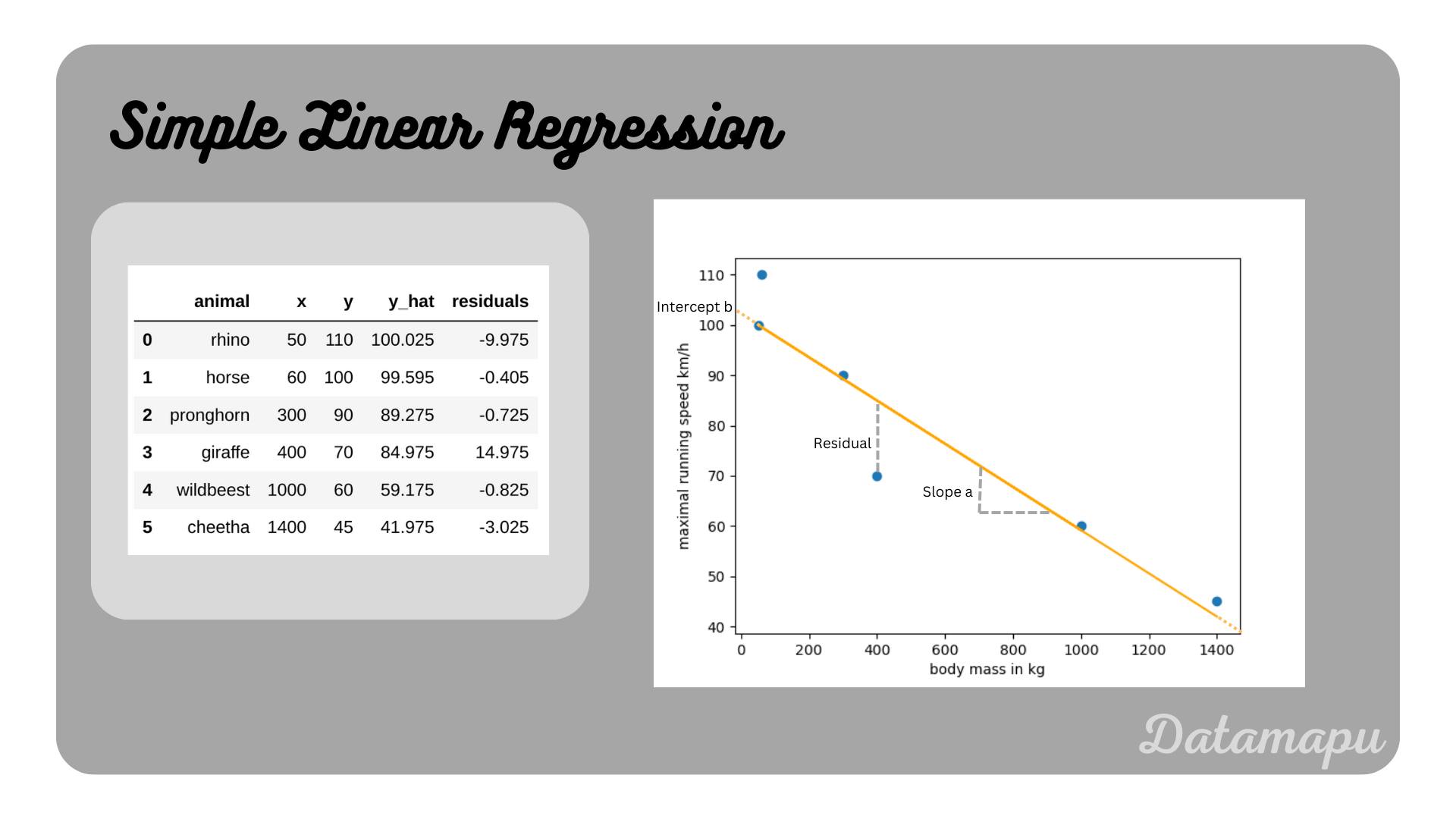

The resulting linear regression model and the original data is illustrated in the following plot.

Note, for this simplified example, we are not going to check the assumptions that need to be fulfilled for a Linear Regression. This example is only for illustration purposes, with this little amount of data statistical tests are not reasonable.

If this blog is useful for you, please consider supporting.