Gradient Boost for Regression - Explained

- 13 minutes read - 2758 wordsIntroduction

Gradient Boosting, also called Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) is a type of supervised Machine Learning algorithm that is based on ensemble learning. It consists of a sequential series of models, each one trying to improve the errors of the previous one. It can be used for both regression and classification tasks. In this post, we introduce the algorithm and then explain it in detail for a regression task. We will look at the general formulation of the algorithm and then derive and simplify the individual steps for the most common use case, which uses Decision Trees as underlying models and a variation of the Mean Squared Error (MSE) as loss function. Please find a detailed example, where this is applied to a specific dataset in the separate article Gradient Boosting for Regression - Example. Gradient Boosting can also be applied for classification tasks. This is covered in the articles Gradient Boosting for Classification - Explained and Gradient Boosting for Classification - Example.

The Algorithm

Gradient Boosting is, as the name suggests, an ensemble model that is based on boosting. In boosting, an initial model is fit to the data. Then a second model is built on the results of the first one, trying to improve the inaccurate results of the first one, and so on until a series of additive models is built, which together are the ensemble model. The individual models are so-called weak learners, which means that they are simple models with low predictive skill. They are only a bit better than random chance. The idea is to combine a set of weak learners to achieve one strong learner, i.e. a model with high predictive skill.

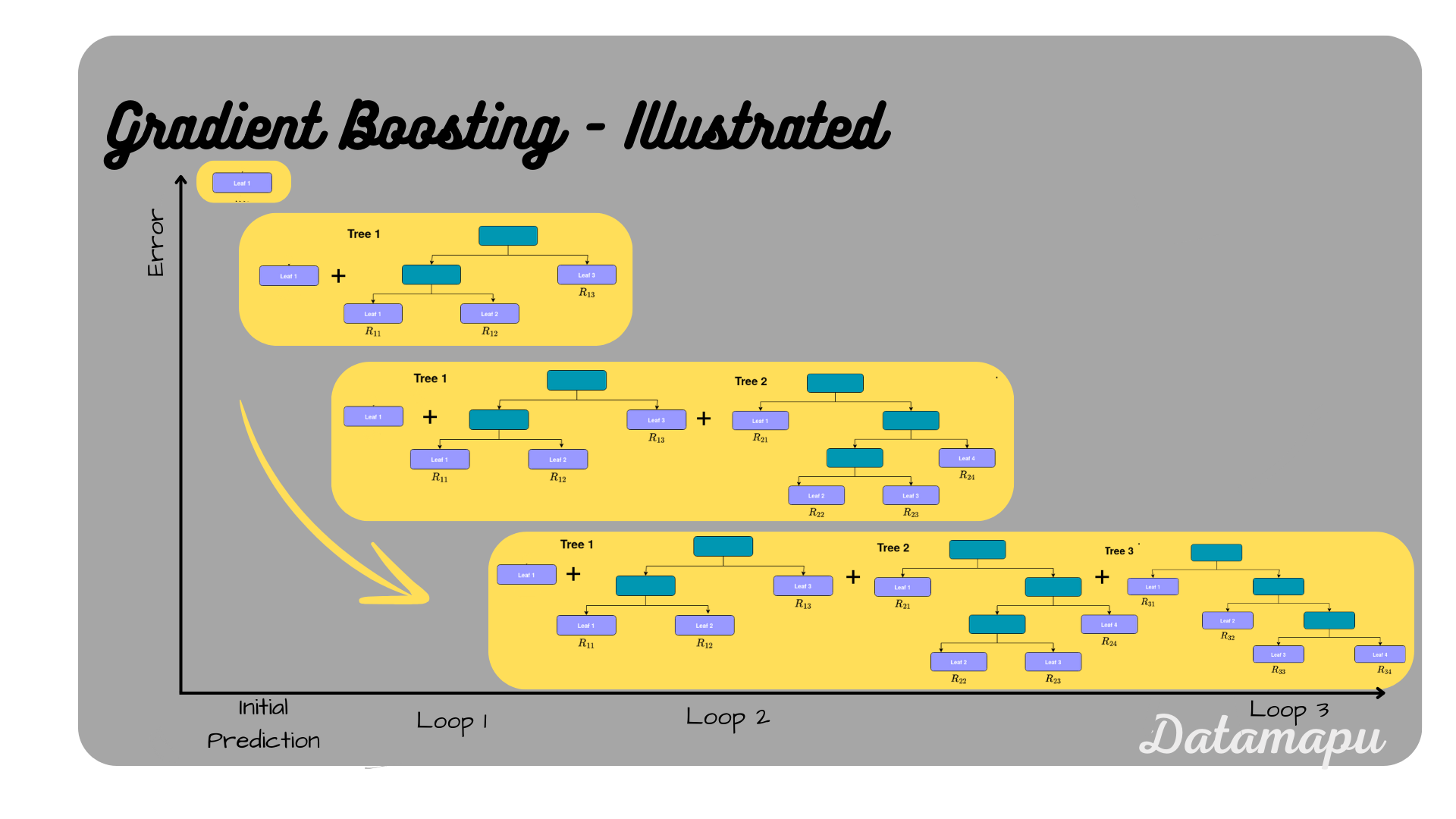

Gradient Boosting illustrated.

Gradient Boosting illustrated.

The most popular underlying models in Gradient Boosting are Decision Trees, however using other models, is also possible. When a Decision Tree is used as a base model the algorithm is called Gradient Boosted Trees, and a shallow tree is used as a weak learner. Gradient Boosting is a supervised Machine Learning algorithm, that means we aim to find a mapping that approximates the target data as good as possible. This is done by minimizing a loss function, that measures the error between the true and the predicted values. Common choices for loss functions in the context of Gradient Boosting are a variation of the mean squared error for a regression task and the logarithmic loss for a classification task. It can however be any differentiable function.

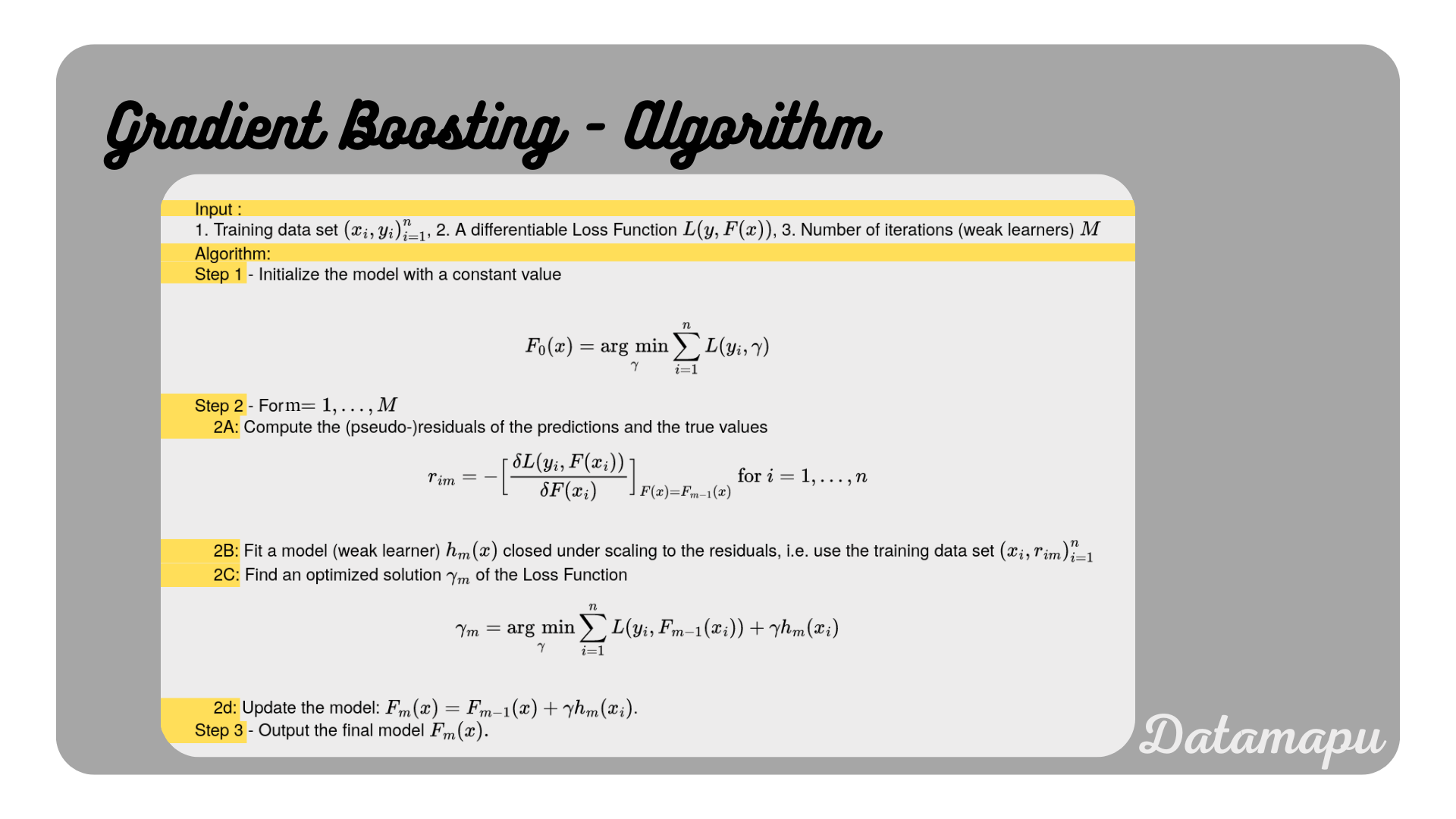

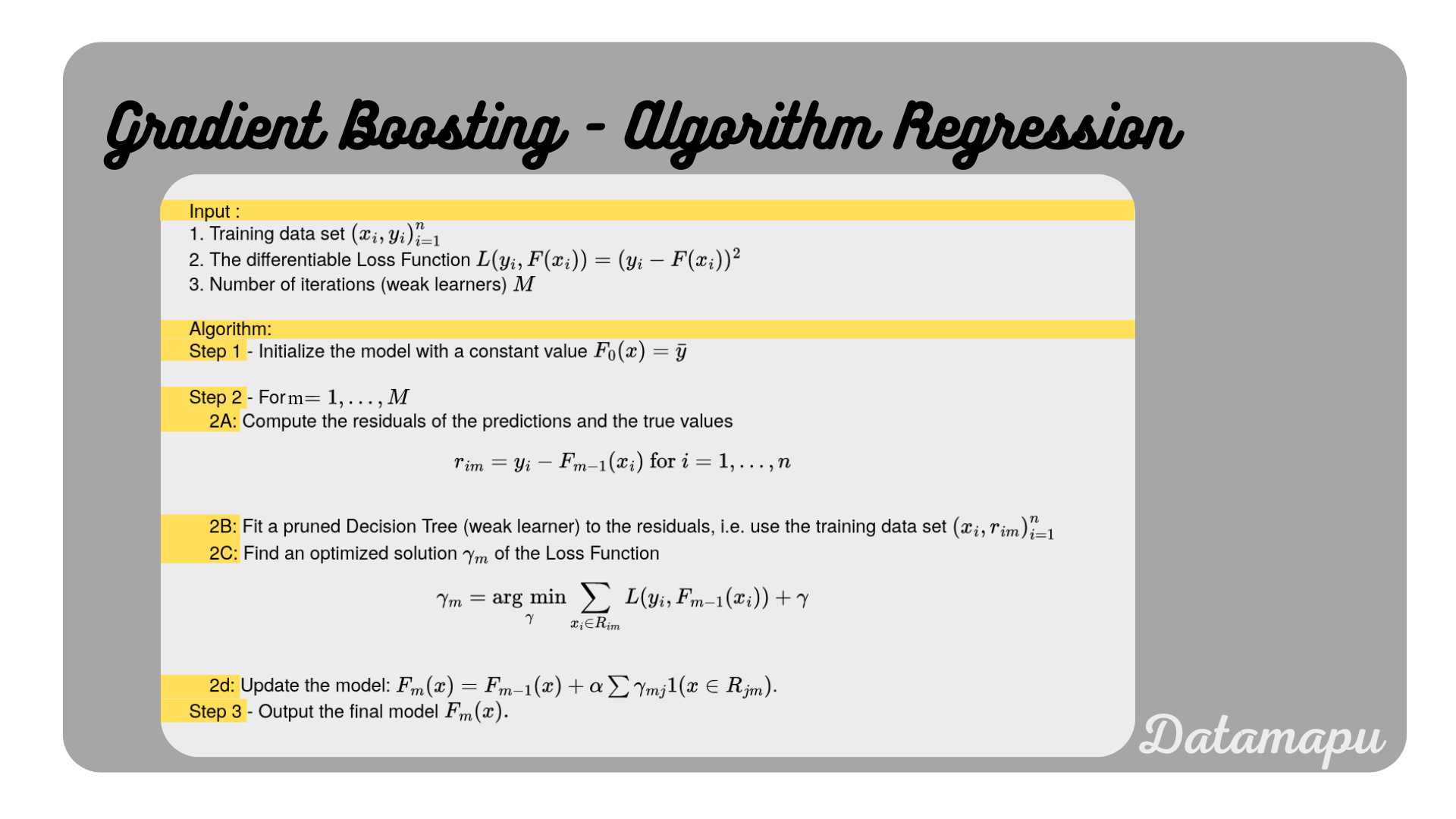

In this section, we go through the individual steps of the algorithm in detail. The algorithm was first described by Friedman (1999)[1]. For the explanation, we will follow the notations used on Wikipedia. The next plot shows the very general formulation of Gradient Boosting following Wikipedia.

Gradient Boosting Algorithm. Adapted from Wikipedia.

Gradient Boosting Algorithm. Adapted from Wikipedia.

We will now take a look at each single step. First, we will explain the general formulation and then modify and simplify it for a regression problem with a variation of the mean squared error as the loss function and Decision Trees as underlying models. More specifically, we use as a loss for each sample

Let

Step 1 - Initialize the model with a constant value -

The initial prediction depends on the loss function (

where

The expression

We set this equal to

That means, for the special loss function we considered, we get the mean of all target values as the first prediction

The next steps are repeated

Step 2 - For

2A. Compute the (pseudo-)residuals of the preditions and the true observations.

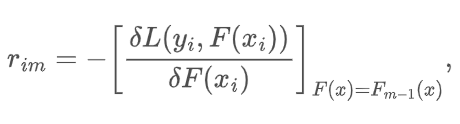

The (pseudo-)residuals

for

Before simplifying it for the special use case, we are considering, let’s have a closer look at this expression. The residuals

Now, let’s see what we get, when we use the loss specified above. Using formula (1a), and

That is, for the special Loss

2B. Fit a model (weak learner) closed under scaling

The next step is to train a model with the residuals as target values, that is use the data

2C. Find optimized solution

The general formulation of this step is described by solving the optimization problem

where

with

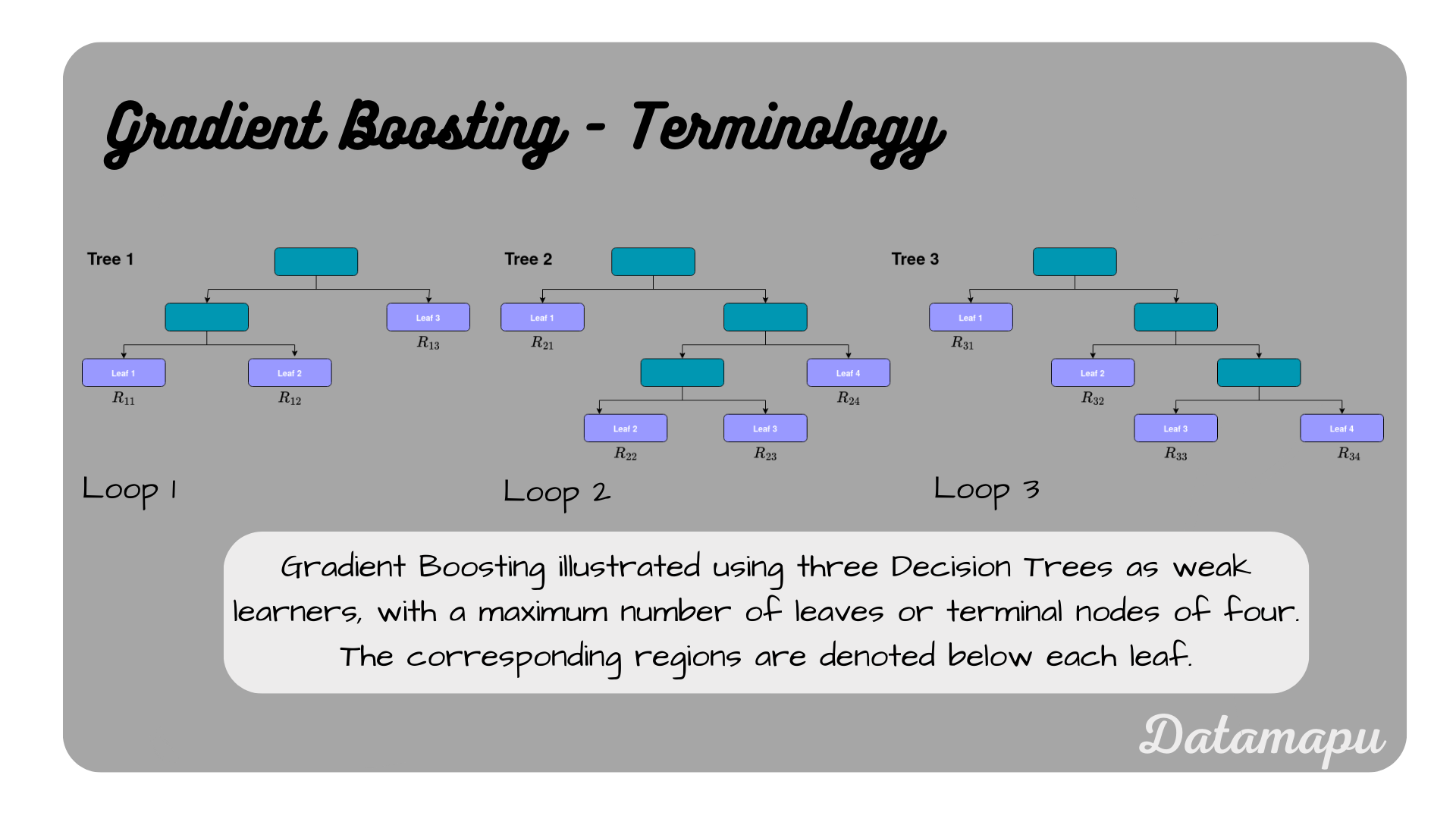

Terminology for Gradient Boosting with Decision Trees.

Terminology for Gradient Boosting with Decision Trees.

For a Decision Tree as an underlying model, this step is a bit modified. A separate optimal value

Note, that the sum is only taken over the elements of the region. For the special case, we are considering using the specified loss

As explained above, this means we want to minimize the right-hand term. For that, we calculate the derivative with respect to

with

with

2D. Update the model.

The last step in this loop is to update the model.

That is we use our previous model

The sum means, that we sum all values

Step 3 - Output final model

The individual steps of the algorithm for the special case of using Decision Trees and the above specified loss is summarized below.

Gradient Boosting Algorithm simplified for a regression task.

Gradient Boosting Algorithm simplified for a regression task.

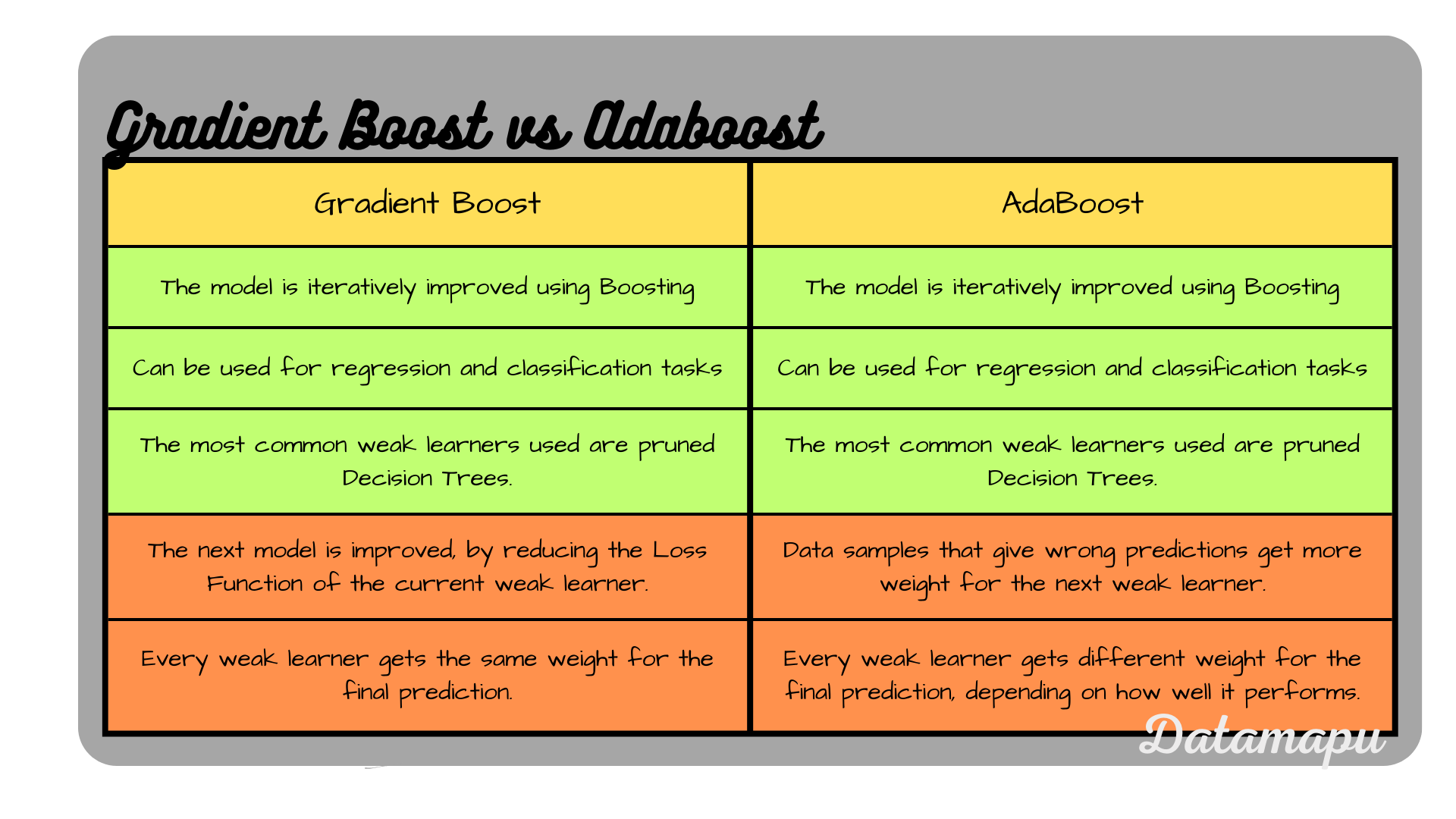

Gradient Boosting vs. AdaBoost (for Regression)

Another ensemble model based on boosting is AdaBoost. Although both models share the same idea of iteratively improving the model, there is a substantial difference in how the shortcomings of the developed model are defined. A comparison of both methods is summarized in the following table.

Gradient Boost vs. AdaBoost.

Gradient Boost vs. AdaBoost.

Pros & Cons of Gradient Boosted Trees

Let’s now see what are the main advantages and disadvantages of Gradient Boosted Trees, as this is the most common application of Gradient Boosting.

Pros

- Gradient Boosted Trees can deal with missing data and outliers in the input features, that is data preprocessing is easier.

- They can are flexible considering the data type of the input features and can deal with numerical and categorical data.

- Gradient Boosting can be applied for regression and classification tasks.

- They are flexible considering the loss function can be used and therefore be adapted to the specified problem.

Cons

- Gradient Boosting may be sensitive to outliers in the target data because every new weak learner (tree) is built on the errors (residuals) of the previous weak learner. Depending on the loss function chosen, outliers may have large residuals. With the loss used in this post, which is a variation of the Mean Squared Error outlier will have high residuals and the next weak learner will focus more on these outliers. Other Loss Functions like the Mean Absolute Error or Huber loss are less sensitive to outliers.

- If the dataset is small or the model too large, i.e. too many weak learners are used Gradient Boosting may overfit.

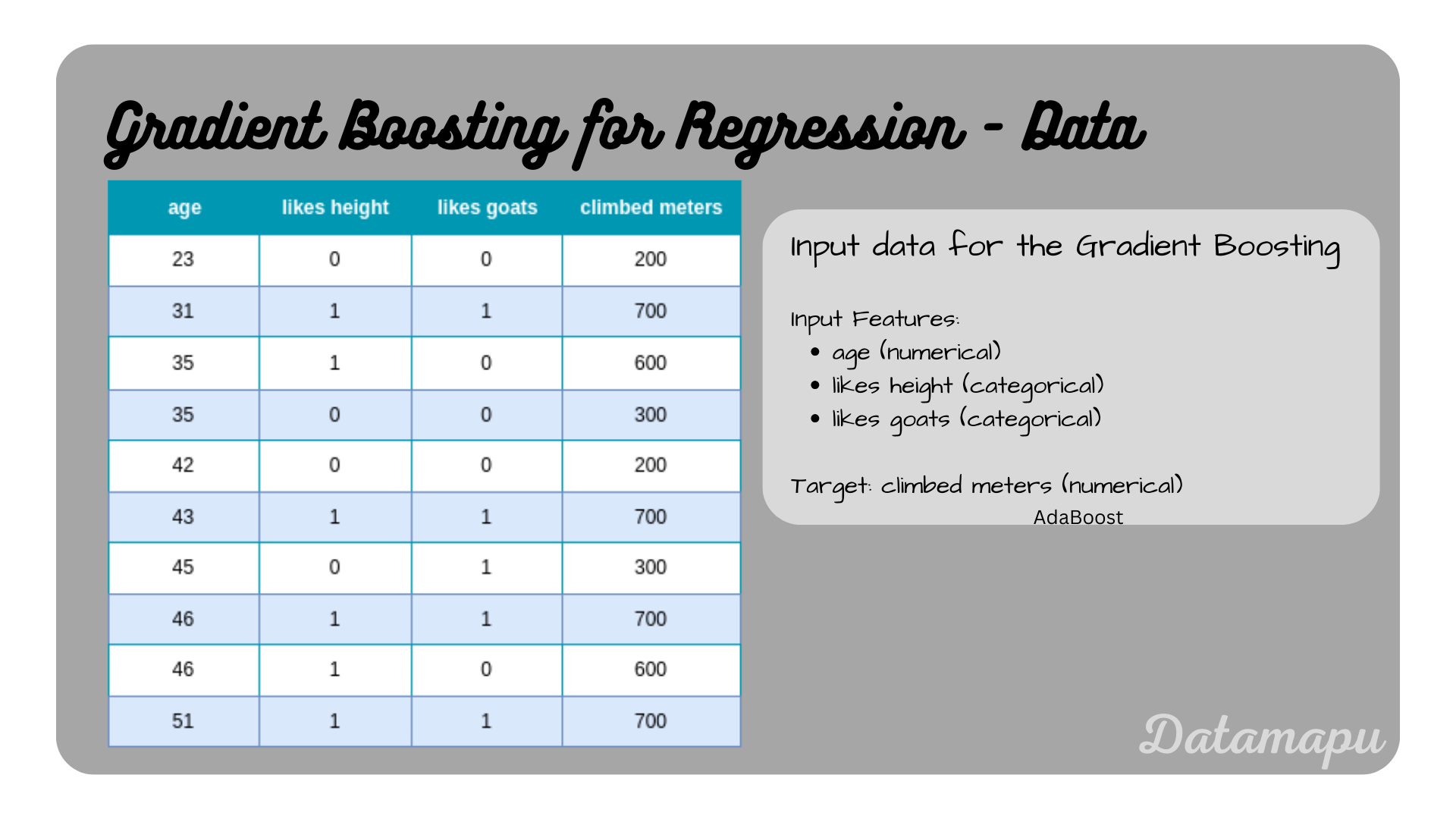

Gradient Boosting in Python

In Python we can use the GradientBoostingRegressor from sklearn to perform a regression task with Gradient Boosting. Note, that the underlying weak learner in this method is not flexible, but is fixed to Decision Trees. Here we consider a very simple example, that contains only 10 data samples. It describes how many meters a person climbed depending on their age and whether they like height and goats.

Dataset considered in this example

Dataset considered in this example

Let’s read the data into a Pandas dataframe.

| |

Now, we can fit a model to this data. There are several hyperparameters available that can be tuned to optimize the model. The most important ones are

loss: Loss Function to be optimized. It can be chosen between: ‘squared_error’, ‘absolute_error’, ‘huber’, and ‘quantile’.. ‘squared_error’ refers to the squared error for regression. ‘absolute_error’ refers to the absolute error of regression and is a robust loss function. ‘huber’ is a combination of the two. ‘quantile’ allows quantile regression (use the hyperparameter alpha to specify the quantile).

Default value: ‘squared_error’.

learning_rate: The contribution of each tree is defined by learning_rate. There is a trade-off between learning_rate and n_estimators. Values must be in the range

Default value:

n_estimators: The number of boosting stages to perform or in other words the number of weak learners. Gradient Boosting is quite robust to overfitting so a large number usually results in better performance. Values must be in the range

Default value: 100.

max_depth: Maximum depth of the individual regression estimators. The maximum depth limits the number of nodes in the tree. If None, then nodes are expanded until all leaves are pure or until all leaves contain less than min_samples_split samples.

Default value: 3.

init: an estimator object or ‘zero’, that is used to compute the initial predictions. The init estimator has to provide a fit and a predict method.If init is set to ‘zero’, the inital predictions are set to zero.

Default value: DummyEstimator, which predicts either the average of the target value (if the loss is equal to ‘squared_error’), or a quantile for the other losses.

alpha: The alpha-quantile of the huber Loss Function and the quantile Loss Function.

Default value: 0.9.

A detailed list of all hyperparameters with explanations can be found in the documentation of sklearn. The pruning of the trees results from the restriction of max_depth in the default setup. We will keep all default values as they are, for this example, except the n_estimators value, which we will set to three. This is done, because our example dataset is very small. In real-world projects, n_estimators is usually much higher.

| |

We can now use the predict method to make predictions and calculate the score of the prediction. The score in this case is the Coefficient of Determination often abbreviated as

| |

This leads to the predictions

Summary

In this article, we discussed the algorithm of Gradient Boosting for a regression task. Gradient Boosting is an iterative Boosting algorithm that builds a new weak learner in each step that aims to reduce the loss function. The most common setup for this is to use Decision Trees as weak learners. We used a variant of the MSE as a loss function and derived the algorithm for this case from the more general formulas. A simple example was chosen to demonstrate how to use Gradient Boosting in Python. For a more realistic example, please check this notebook on kaggle.

Further Reading

- [1] Friedman, J.H. (1999), “Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine”

- [2] Wikipedia, “Gradient boosting”, date of citation: January 2024

If this blog is useful for you, please consider supporting.